Add Heading

One evening towards the end of the 1980s I scrambled onto the top deck of a bus going from BMA House to Waterloo. There was only one other person on the top of the bus: a man in a business suit holding an unfamiliar piece of equipment about the size of a shoe. He raised it to his face and started talking.

I had heard of these new-fangled telephones that ran on batteries so that you could call up your loved one (or your stockbroker) wherever you happened to be. This was clearly one of them. I expressed admiration for his gadget, and he offered to let me have a go. I dialled our home in Leatherhead and spoke to Barbara.

‘I am on the top of a bus’, I said, by way of introduction.

We marvelled about our conversation when I got home and wondered whether it would catch on.

Changes were coming thick and fast in the 1980s, but most of us were slow to realise how much they would change our lives.

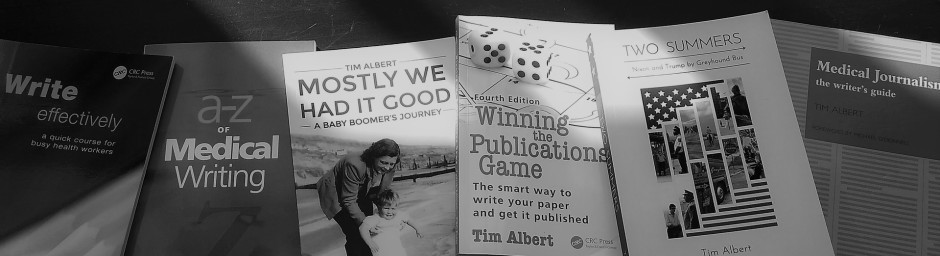

One exception was Dr Hugh Glanville, a writer and editor of some note, who was one of the first to buy a word processor. In 1981, when I was at World Medicine, we ran an article by him describing

a wondrous, new possession: a word processor.

‘I type on a typewriter-style keyboard and the words appear on a small screen, disappearing off the top (into the computer’s memory) a few lines at a time when I add more text at the bottom. The most

elementary advantage is that mistakes do not matter. I simply overtype them, which is nice if like me you are not a very good typist. Nimble typists take advantage of this and go really fast,

correcting any mistakes later. A winking square called the “cursor” can be moved about the screen and positioned anywhere and used to change a letter, delete it, or create a space for one that has

been left out.

Word processing programs, however, allow a much more flexible editing than just correcting errors. Any word, line, sentence, paragraph or page can be deleted, or picked up and moved somewhere else,

or even reproduced elsewhere without being deleted. This electronic cut-and-paste facility enormously simplifies original writing, revising, and editing. I drafted this article several times before I

was content with it, but at the end I wasn’t left with any multiply amended stick-taped draft to be typed out; I just had to press a button for the final version.’ (Hugh de Glanville, My New Right

Hand, World Medicine, October 17, 1981)

There was more. You could search the entire text for any word and number and change it, or store addresses, or sort lists - all for a cost of £1,500 plus VAT for word processor and attendant

printer. In time, he predicted, these machines would provide a complete electronic filing system on the top of a desk, containing accounts, addresses, practice records, research papers and much else.

And the largest leap of all: we would be able to exchange information via telephone lines to other word processors.

‘They are likely to take over from straight typewriters much as electric machines took over from manuals – that is to say, in Britain, slowly,’ he wrote.

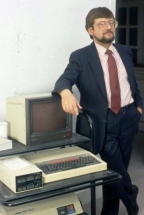

Three years later, when I arrived at the BMA, talk about word processors had been superseded by talk of personal computers. I didn’t really understand what they did and how they worked, but I sensed

that they would be important. My new colleague Dr John Dawson, head of science at the BMA, was an early enthusiast, so I asked him to write a column.

His first, in May 1984, warned that there would be abuses and they would need to be controlled. His second flagged up the development of a BMA database (I had little idea of what that really meant)

which would gather and keep daily summaries of press cuttings on health care.

Not long after, he went out to Africa with a Land Rover full of electronic quipment. Once there, and in the middle of the bush, he managed to receive on his computer messages from back home in

England. He wrote:

‘A satellite communications terminal can cost less than a modest medical and nursing library and can give access to large quantities of information. The ... searching software can track down material

in a fraction of a second that a skilled human librarian might take hours to find.’ (BMA-NR January 1985).

I published the story but couldn’t yet see the point.

John Dawson became manager of the BMA Library and soon he introduced changes. The old-school librarian, who proudly donned gloves to show me ancient manuscripts in his care, soon left. In his place

came Tony McSean, a younger man who had worked as a teacher, journalist and rock band manager before training as a librarian. He sometimes wore a white suit to work and he certainly understood

computers.

His goal was to make the library accessible to members sitting at home or in their offices, and he organised courses showing doctors how to search databases and gather the information they needed. We

sent a reporter on one of these courses, who reported her conversion from nervous Luddite to convenient enthusiast:

‘In future it will be feasible to tap these databases from the computer on one’s desk at home, in the hospital or the surgery...You can even carry a portable computer to the wilds and

connect...through a local phone box’ (Julia Bland, Fighting the fear of new technology, BMA-NR July 1988).

On the magazine our own working practices started to change. I bought some computers for the magazine and we used them to write out copy. Our sub-editor then inserted codes so that they no longer

needed to be keyed in a second time.

A few years later we took the next step and installed a fancy programme called Windows – plus another fancy programme called Pagemaker that allowed us to go one step further and lay out pages

ourselves. The BMA computer buffs had urged caution, but we decided to go ahead anyway, on the grounds that it would take them three years to make up their minds, by which time any new system would

have needed updating anyway.

I was happy to approve these leaps into the future, but my own competence was limited. I identified with one early correspondent who reported being told at a conference: ‘The silicon chip is the

answer. But what is the question?’

On several occasions I made an observation that in hindsight seems the height of foolishness. Because BMA News Review was an integral part of the BMA, we

regularly got to hear of breaking medical stories long before our rivals got to do so. Sadly this gave us no advantage whatsoever because, as a fortnightly, we usually had a long wait until our

publication reached its audience.

‘If only we could find a way of writing the magazine one day and without too much expense delivering it on the next’, I would muse. I had no idea what was just around the technological corner.

Here's where you can enter in text. Feel free to edit, move, delete or add a different page element.